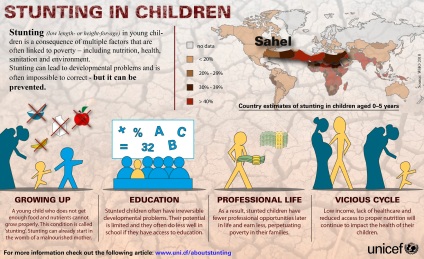

Addressing the issue of stunting or chronic undernutrition, resulting in growth retardation, is currently a big issue because it affects dramatically children’s development and compromised irremediably their future professional life.

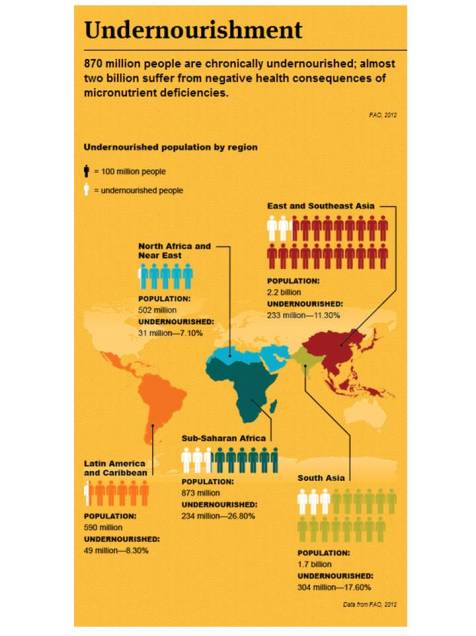

As announced last week by the EU Commissioner for development, Andris Piebalgs: “Undernutrition is the biggest threat to people’s health in the developing world, causing at least one third of all child deaths, and a fifth of mothers. This shocking and shameful reality calls for an improved, global and decisive response. The EU is firmly committed to reduce by 7 million the number of stunted children by 2025. Increased international mobilization is vital. That’s why, today, I am also calling on other major donors and development actors to join us in this global movement and make their own commitments.”

When I decided to embark in this journey, I didn’t know that I would spend days reading articles, analyzing, pondering the pro and con… My personal objective was to be able to put together different pieces of the puzzle to really understand how we can impact poverty through preventing stunting and as a result, ensuring a dignified future for everyone. One of my lesson learnt is the fact that we need to change our mindset … Access to food is not only based on quantity (calories) but it is more importantly based on quality (micronutrients for sure, but also macronutrients) when nutrition becomes the corner stone of global health and food security. This change in mindset is the future of sustainable human development not only in the developing world but also in the developed countries.

This article will review different aspects to help us to better understand the issue of stunting (and its adverse outcomes) not only in children but also in women. A short stature can predict more than one dimension of the potential impact that malnutrition can have on human being — it is why it is so critical to address this issue appropriately.

The current situation – a decrease of the incidence of stunting, yes but not for everyone:

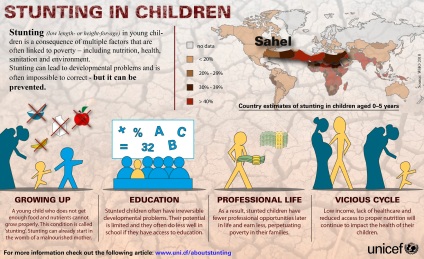

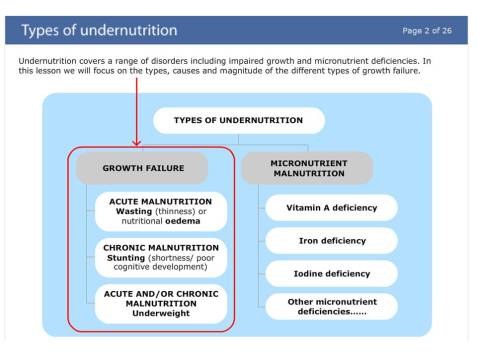

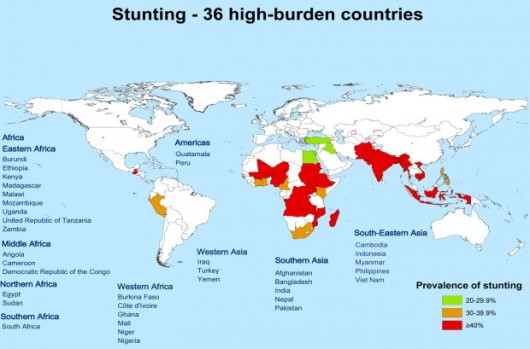

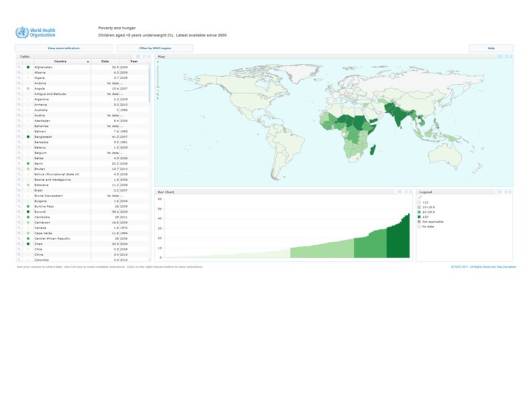

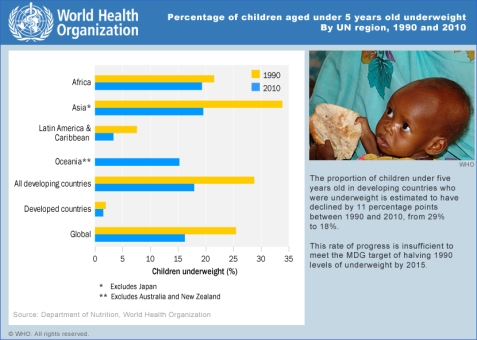

The children who are suffering from stunting (short stature) may look normal but their brain development and immune systems most certainly are not. Stunting is much more common than underweight (low weight-for-age) or wasting (low weight-for-height), affecting globally in 2010 about 171 million or 27% of children aged 0–5 years.

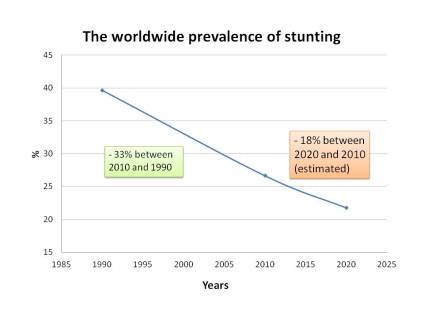

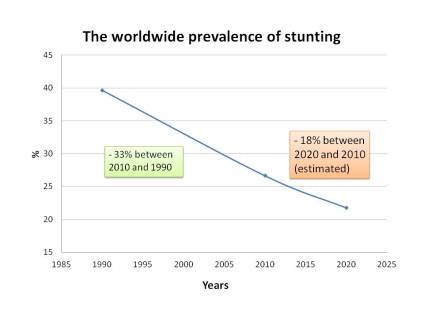

The good news … Worldwide, the prevalence of childhood stunting has decreased and will continue to decrease as shown in the figure below:

(Adapted from Maternal and Child Nutrition (2011), 7 (Suppl. 3), pp. 5–18)

Trends in stunting follow different patterns in developing and developed countries. While the prevalence of stunting in developed countries has been stable at 6% since 1990 and is expected to remain at this level, developing countries have experienced a decrease from 44.4% in 1990 to 29.2% in 2010. The prediction is that this decreasing tendency will continue and will reach a prevalence of 23.7% in 2020.

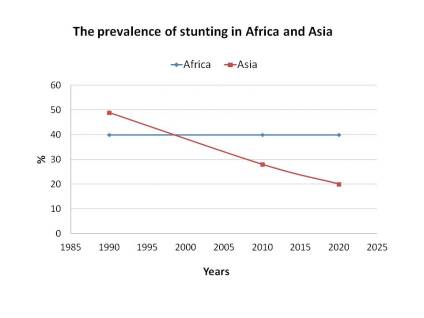

Africa vs Asia – not the same story:

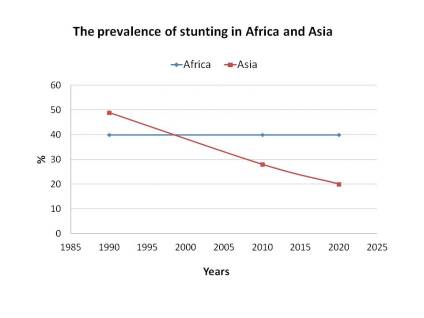

(Adapted from Maternal and Child Nutrition (2011), 7 (Suppl. 3), pp. 5–18)

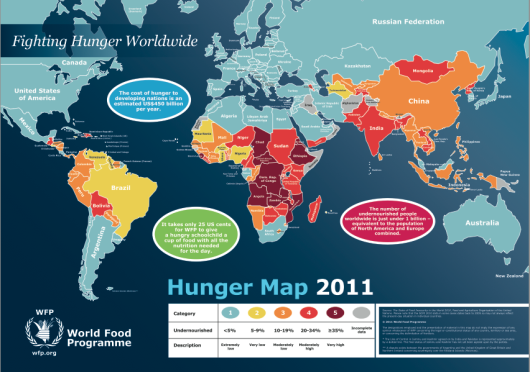

In Africa, given population growth, the result presented above has translated into increasing numbers of stunted children (from 45 million in 1990 to 60 million in 2010). In contrast, Asia has showed a dramatic decrease and this declining trend will continue, reaching a total number of stunted children in Asia (68 million) similar to the number in Africa (64 million) in 2020. In Latin America both the prevalence and number of affected children were much lower than in Africa and Asia (14 % or 7 million in 2010) and they are expected to continue decreasing in the coming decade). Data in Oceania remain scarce and thus trend modeling is not possible. However, individual countries like Papua New Guinea show high rates of stunting (44 % in 2005).

There is a great variation in rates of childhood stunting among countries. The figure above maps countries according to their latest national stunting prevalence estimation. Extremely high rates appear in countries like Afghanistan, Yemen, Guatemala, Burundi, Madagascar, Malawi and Ethiopia, with levels closed to or above 50 % in most recent surveys. Other countries of sub-Saharan Africa, South-central and South-eastern Asia also present high to medium stunting rates.

The causes – inadequate dietary intake but also disease like infection and diarrhea:

The causes and etiology of stunting are the result of multiple circumstances and determinants. To schematize, the immediate determinants refer to inadequate dietary intake and disease. The underlying determinants include food insecurity, inappropriate care practices and an unsafe environment including access to water and hygiene, inadequate health services and air pollution. A new determinant that has received a lot of attention over the past few years is mother-infant interaction (maternal nutrition and stores at birth, and behavioral interactions). All these circumstances result in increased vulnerability to shocks and long term stresses.

(Sphere project – http://www.sphereproject.org/)

In actual fact, the determinants of undernutrition are rooted in poverty and involve interactions between social, political, demographic, and societal conditions. Over the past decade, It became important to go beyond the traditional concept of food security (access, availability, stability and utilization of food) and recognizes that the nutritional status is dependent on a wide and multi-sectoral array of factors. It is why the international community has starting to introduce the concept of nutrition security because …

A household can achieve nutrition security only when it has secure access to food coupled with a sanitary environment, adequate health services, and knowledgeable care to ensure a healthy life for all household members.

But it is important to remind that stunting is a complex issue. The causes and etiology of stunting are much less understood than are its timing and consequences. In particular, there is little understanding of why and how stunting occurs extensively in environments that are poor, but not desperately so, and in environments that seem to be improving (India is the good example). In a population, an individual child can become stunted or not. In addition, some populations are much more stunted than others. This means that an understanding of why and how children become stunted is needed at both the individual and ecological levels.

The consequences – a dramatic long term impact that affects human capital:

The consequences of becoming and remaining stunted are increased risk of morbidity, mortality, delays in cognitive (ability to think and understand) and physical development, and decreased work capacity. Actually, it is well documented that impaired mental and physical development has long-term negative consequences on both micro and macro levels, reducing human and overall economic development. The economic cost of undernutrition has been estimated at 2 to 8 % of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Moreover, children who have suffered of malnutrition (stunting) during their childhood are also at higher risk of suffering from chronic diseases (such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease) in adulthood. As highlighted in one of the latest Lancet Series “The global burden of diseases study 2010“: fewer children are dying every year (big progress), but more young and middle-aged adults are dying and suffering from disease and injury, as non-communicable diseases (cancer and heart disease) that become the dominant causes of death and disability worldwide: 54% of disability-adjusted life years worldwide were caused by non communicable disease in 2010, compared with only 43% in 1990.

The vicious inter-generational cycle of malnutrition = the inter-generational transmission of poverty:

Although a child may not be classified as ‘stunted’ until 2–3 years of age, the process of becoming stunted typically begins in utero. The result – a very short height – usually reflects the persistent, cumulative effects of poor nutrition and other deficits that often span across several generations (see figure below).

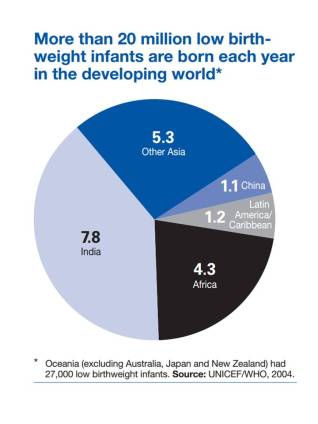

Poor nutrition often starts in utero and extends, particularly for girls and women, well into adolescent and adult life, and extends over to the next generations. The infants with low body weight, who suffered intrauterine growth retardation, and born undernourished, are at higher risk of dying in the neonatal period or later infancy. If they survive, they are unlikely to significantly catch up on this lost growth later and are more likely to experience a variety of developmental deficits. In fact, an infant with low body weight at birth (which is strongly correlated with birth length) is thus more likely to be underweight or stunted in early life.

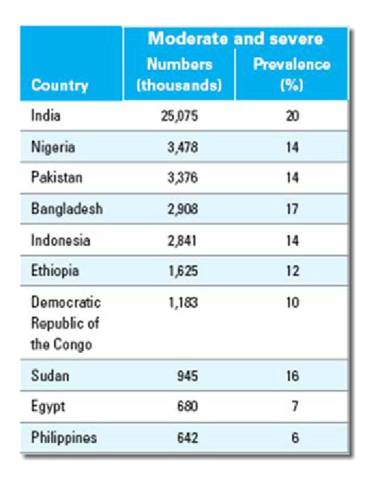

Actually, stunting can be found at many levels in society. In Bangladesh, for example, stunting in children less than 5 years of age was found in one-fourth of the richest households [National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), 2009]. In developing countries, stunting is more prevalent than underweight (low weight for age, 20%) or wasting (low weight for height, 10%), possibly because height gain is even more sensitive to dietary quality than is weight gain.

Stunted height is a dreadful marker of multiple deprivations regarding food intake, care and play, clean water, good sanitation and health care. As a result, stunting is an important indicator of child well-being and is considered as a marker of endemic poverty.

To summarize, it is important to remember that small size at birth and childhood stunting are linked with:

- short adult stature,

- reduced lean body mass,

- less schooling,

- diminished intellectual functioning,

- reduced earnings, and

- lower birth weight of infants born to women who themselves had been stunted as children

These outcomes have long-term impact if not addressed appropriately.

The figure below presents the % of low infant birthweight. The highest % is observed in 3 of the countries where we also observe a high incidence of short maternal stature, i.e. Afganistan, Yemen and Ethiopia. Sub-Sahara Africa (and specifically the Sahel region) and South East Asia are the regions where we observe the higher prevalence of low infant birth weight and stunting (see world map on prevalence of stunting above).

The importance of maternal malnutrition (short stature and/or low body weight) – a key issue in the context of sustainable human development:

We now all agree that adult height in women reflects a cumulative outcome measure of environmental exposures from fetal to adult life encompassing nutritional, infectious, socio-cultural, and economic influences that can be transmit to the next generation through the inter-generational cycle of malnutrition. In this context, investing in women can have an astonishing impact!

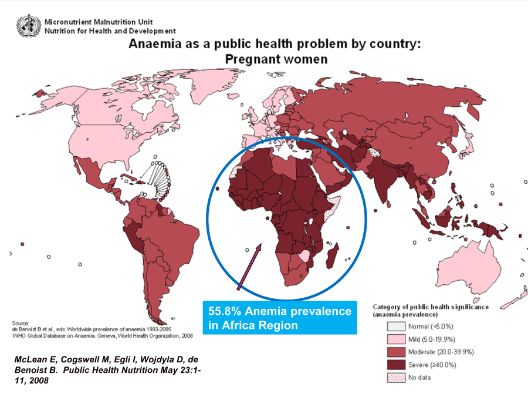

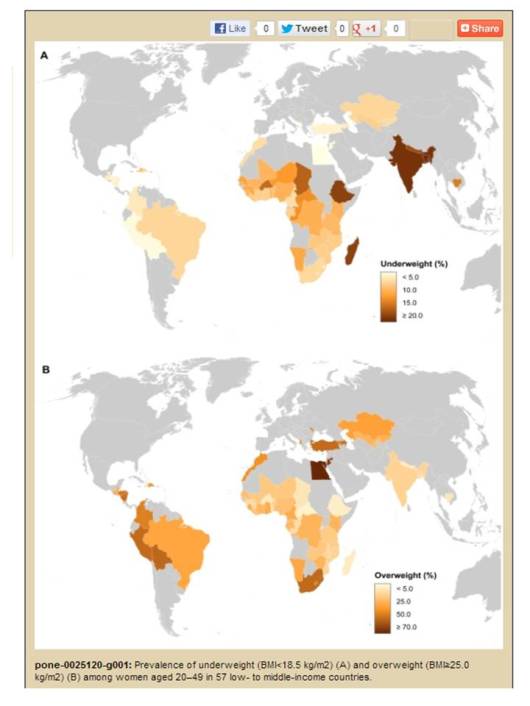

Maternal undernutrition, embodied by short stature and a low body mass index (BMI), is highly prevalent in many developing countries. Short stature (<145 cm) affects more than 10% of women of reproductive age across South Central Asia and Latin America, but only 1% to 2% in sub-Saharan Africa, whereas a low BMI (<18.5) is found among 20% or more women in sub-Saharan Africa and South Central Asia but not in Latin America.

It was really interesting to go through the scientific publications & international agency reports to better understand this issue. More I was reading about this issue, more I was conscious of what are the overwhelming consequences of maternal chronic undernutrition in the context of child and maternal health, and how it is crucial to invest in women nutrition, health, education and empowerment. Let me to put together some numbers, facts and of course, maps/graphs to help us to better understand the problem.

Because the consequences of maternal malnutrition (mortality and morbidity) in the context of pregnancy are dramatic…

Both indicators (short stature and low BMI) can predict adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, only

- Maternal height is a strong predictor of birth size, and

- It is inversely associated with risks of child mortality, underweight, stunting, and wasting

From a clinical point of view, short maternal stature can restrict uterine blood flow and growth of the uterus, placenta and fetus. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is associated with many adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes like chronic fetal distress or fetal death. Moreover, short maternal stature is consistently associated with an elevated risk of perinatal mortality (stillbirths and deaths during the first 7 days after birth), mostly related to obstructed labor resulting from a narrower pelvis in short women. In a hospital based study in Nigeria, obstructed labor accounted for 53% of perinatal mortality that is largely the result of birth asphyxia.

The world map below shows the cause of under 5 mortality for the World Health Organization region. Neonatal causes of death (the yellow part of the disk) represent more than 40% of all causes of death in all the regions, except Africa (brown color).

Globally, birth asphyxia accounts for 23% of the four million neonatal deaths each year. An estimated one million children who survive birth asphyxia live with chronic neuro-developmental disorders, including cerebral palsy, mental retardation and learning disabilities (World Health Organization 2005).

Interestingly, the effect of short maternal stature on child mortality is comparable to the effect of having no education or being in the poorest 20% of households.

Moreover, short maternal stature because of the risk of disparity in size between the baby’s head and the mother’s pelvis increases also the risk of maternal mortality and short and long-term disability. The consequences of obstructed labor include injury to the birth passage, postpartum hemorrhage, rupture of the uterus, genital sepsis or fistula, leading to urinary dribbling or incontinence (see the documentary: A walk to beautiful – http://ww3.tvo.org/video/162183/walk-beautiful). In the worst case scenario, obstructed labor can lead to maternal death, mostly because of ruptured uterus or puerperal sepsis.

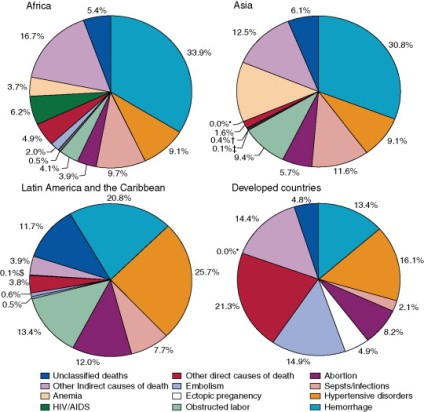

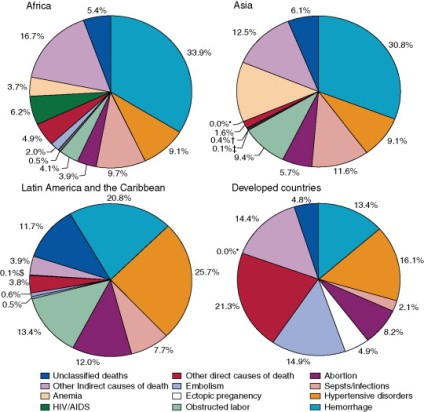

Causes of maternal death (World Health Organization – 2008)

The percentages of maternal mortality attributable to obstructed labor (grey color) are 4% in Africa, 9% in Asia and 13% in Latin America and the Caribbean. Mothers who survive but have long-term disability due to complications such as fistula experience social, economic, emotional and psychological consequences that have an enormous impact on maternal health and well-being.

Finally, lower birthweight (which is strongly correlated with birth length) and undernutrition in childhood are risk factors for high glucose concentrations, blood pressure and harmful lipid profiles in adulthood. The “developmental origins of health and disease” (or Barker) hypothesis hypothesizes that the intrauterine and early post-natal environment can modify expression of the fetal genome and lead to lifelong alterations in metabolic, endocrine and cardiovascular function. In this case, it is likely that the process of stunting is harmful and not necessarily short stature itself.

Let me to put some perspective because the numbers talk by themselves….

Compared with the highest maternal height category of more than 160 cm, women with short stature (<145 cm) have an approximately 40% higher risk of any of their offspring dying, after adjusting for confounders.

A similar analysis revealed risks of stunting and underweight in offspring to be 2-fold greater among short mothers, whereas that of wasting was only 17% higher.

However, with every 1-cm increase in height, the relative and absolute risk of each of the adverse outcomes listed above (i.e. child mortality, underweight, stunting, and wasting) can be significantly decreased.

The “window of opportunity” for improvement – yes, it is possible to change things:

During fetal life and the first 2 years after birth (the famous 1000 days), nutritional requirements to support rapid growth and development are very high.

Envision! … The first year of life is a time of astonishing change during which babies in normal conditions, on average, grow 55% in length, triple their birth weights and increase head circumference by 40%. Between 1 and 2 years age, an average child grows about 12 cm in length and gains about 3.5 kg in weight. A costly process!

During these crucial days as well as during fetal life, the body is putting together the fundamental human machinery (similar to hardware and software for computer). This process is done over a very short period of time, with demanding nutrient requirements. Immune-system and brain-synapse development are particularly vulnerable. As a result, any disturbance of this frantic activity leaves a terrible mark.

In this context chronic malnutrition can have a dramatic impact. Then, let me discuss the importance of nutrition for both immune-system and brain-synapse development. We will take the opportunity to highlight the importance of diversified nutrition (macro as well as micronutrients intake) in the context of “in 1000 days you can change the future” (http://www.thousanddays.org/).

In the case of brain-synapse development, which nutrients are important?

Growth factors, but also nutrients regulate brain development during fetal and early postnatal life. The developing brain between 24 and 42 wk of gestation is particularly vulnerable to nutritional insults because of rapid neurologic processes, including synapse formation and myelination. All nutrients are important for neuronal and glial cell growth and development, but some appear to have greater effects during the late fetal and neonatal life. These include protein, iron, zinc, selenium, iodine, folate, vitamin A, choline, and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. The effect of nutrient deficiency or supplementation on the developing brain is a function of the brain’s requirement at a specific time for a nutrient in specific metabolic pathways and structural components. For example, during late fetal and early neonatal life, regions such as the hippocampus, and the visual and auditory cortices are undergoing rapid development characterized by the morphogenesis and synaptogenesis that make them functional. In this case, protein-energy and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids are important.

For any given region, early nutritional insults have a greater effect on cell proliferation, thereby affecting cell number. Later nutritional insults affect differentiation, including size, complexity, and in the case of neurons, synaptogenesis and dendritic arborization (the neuronal circuit that permits to send information).

All nutrients are important for brain development, but some appear to have a particularly large effect on developing brain circuits during the last trimester and early neonatal period as shown in the table below:

Important nutrients during late fetal and neonatal brain development

(Adapted from Am J Clin Nutr February 2007 vol. 85 no. 2 614S-620S)

|

Nutrient

|

Brain requirement for the nutrient

|

Predominant brain area or activity affected by deficiency

|

|

Protein-energy

|

Cell proliferation, cell differentiation

Synaptogenesis

…

|

Global

Cortex

…

|

|

Iron

|

Myelin

Neuronal and glial energy metabolism

…

|

White matter

Hippocampal-frontal

…

|

|

Zinc

|

DNA synthesis

…

|

Autonomic nervous system

…

|

|

Copper

|

Neurotransmitter synthesis, neuronal and glial energy metabolism, antioxidant activity

|

Cerebellum

|

|

Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids

|

Synaptogenesis

Myelin

|

Eye

Cortex

|

|

Choline

|

Neurotransmitter synthesis

Myelin synthesis

…

|

Global

White matter

…

|

Breast feeding is the best food in this context…

The potential mechanisms through which breastfeeding may improve cognitive development relate both to the composition of breast milk and to the experience of breastfeeding. Breast milk contains a suite of nutrients, growth factors, and hormones that are important for brain development, including critical building blocks such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA – fish oil) and choline. In addition, the physical act of breastfeeding may promote the quality of the mother-infant relationship and enhance mother-infant interaction, which are important for cognitive and socioemotional development. For instance, cognitive effects of nutritional deficiencies (as measured by the mental development index of Bayley Scales) are more severe for children living in homes where there is less stimulation compared to homes with higher levels of stimulation.

When compared to formula, human milk provides all the essential n-6 and n-3 PUFA like linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid, as well as their longer-chain more-unsaturated metabolites, including arachidonic acid and DHA that support the growth and development of the breast-fed infant. In fact, the role of DHA in infant nutrition is of particular importance because DHA is accumulated specifically in the membrane lipids of the brain and retina, where it is important to visual and neural function. In this context, it is crucial to ensure an adequate maternal dietary lipids and DHA intake if this is the only source of essential fatty acids for infant development both before and after birth to minimize the risk of low infant neural system maturation.

In this case, investing in programs that focus on exclusive breast feeding during the first 6 months, that will continued along with appropriate complementary foods up to two years of age as well as increased access to nutritious food for breastfeeding mothers makes sense because these strategies will pay back…

In the case of immune-system development, which nutrients are important?

Immune cells and organs rapidly proliferate in the first trimester of pregnancy. Early cells undergo progressive waves of maturation, some unique to the fetal period, as they build the capacity to recognize and adapt defenses to specific pathogens. Although the immune system is qualitatively complete at birth (but still immature), exposures to colonizing commensal bacteria, environmental antigens, bioactive dietary substances, and potential pathogens during infancy and early childhood are essential for expansion and priming of adaptive cell populations. These critical periods of development are highly vulnerable to insult, which may permanently alter immune defenses.

Moreover, the ability of the immune system to prevent infection and disease is strongly influenced by nutritional status of the host. In fact, malnutrition is the most common cause of immunodeficiency in the world. Nutrient deficiencies can cause immunosuppression and dysregulation of immune responses. Because nutritional status can modulate the actions of the immune system, the sciences of nutrition and immunology are tightly linked.

Impact of maternal malnutrition in infant immune system development:

The impact of maternal protein-calorie malnutrition (PCM) on neonatal vulnerability to infectious disease is well known. Much of the damage to neonatal host defense occurs through impact on the developing immune system, especially the thymus, often called the barometer of nutrition. In this context, malnourished children have lower levels of thymulin* and deficient T-cell development.

Micronutrient imbalance or deficiency in the mother in the absence of PCM can alter the program of immune development in the infant. The strongest evidence for micronutrient programming effects comes from studies of vitamin A deficiency. In fact, vitamin A is required for the homing of T cells into the gastrointestinal tract and promotion of antigen-specific regulatory T cells development.

Impact of malnutrition in infant:

PCM primarily affects cell-mediated immunity (increased phagocyte activity, cytotoxic T cells activation and cytokine release) rather than humoral immunity (antibody response). In particular, PCM leads to atrophy of the thymus, the organ that produces T cells, which reduces the number of circulating T cells and decreases the effectiveness of the memory response to antigens. Additionally, PEM compromises the integrity of mucosal barriers, thereby increasing susceptibility to infections of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urinary tracts. PCM often occurs in combination with deficiencies in essential micronutrients, especially vitamin A, zinc, copper, selenium, and magnesium.

The good news is that the effects of PCM are reversible by refeeding. Renutrition studies in children showed that innate immune functions and adaptive lymphocyte proliferative response improve in parallel with growth. Treatment of severely malnourished infants has shown that after refeeding, previously deficient phagocytosis, microbicidal activity, chemotaxis, and cell proliferation indices normalized along with anthropometric gains.

Micronutrient deficiencies are a major complication of PCM and promote infectious processes. Oxidative stress is worsened in infection if micronutrients are deficient. Vitamin A, β-carotene, folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin C, riboflavin, iron, zinc, and selenium have immunomodulating functions and influence both the susceptibility of the host to infectious diseases and the course and outcome of these diseases. For example, vitamin A deficiency impairs mucosal barriers and diminishes the function of neutrophils, macrophages, and NK cells.

And again …Breast feeding is the best food in this context…

Human milk provides virtually all the protein, sugar, and fat baby needs to be healthy. It also enhances the immature immunologic system of the neonate and strengthens host defense mechanisms against infective and other foreign agents. Some mechanisms that explain active stimulation of the infant’s immune system by breastfeeding are the bioactive factors in human milk such as hormones, growth factors and colony stimulating factors, as well as specific nutrients like lactoferrin, one of the most abundant proteins in human milk, nucleotides, complex sugars and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

To conclude…

Simply providing an adequate food supply likely would not be enough to keep kids growing well. Researchers said that common childhood incidents in the developing world, such as a high burden of early childhood infections (acute diarrhea and infection with a parasite), compound the problem. Both diarrhea and parasites can lead to malnutrition—and vice versa—so the path to well-nourished, healthy children is not quite as simple as making sure that their families have enough food.

To have an impact on stunting levels, nutrition-sensitive interventions (bringing quality and not only quantity) and promotion of adequate nutrition practices need to be targeted to women during pregnancy and to children from birth to 24 months of age. In addition, communities require increased income among the poor, improved food security, sanitation and water supplies as well as better public health education and health care availability. Investment in these changes in the near term should pay off later in improved earning power and an easier ascent out of poverty, which in turn should also lead to better health for the generations to come.

Moreover, tackling undernutrition will require solutions to be developed with the integration of the food security, livelihoods, health, care practices and nutrition sectors. Yet, the linkages between the different sectors are complex and are increasingly under scrutiny as experience has shown that each sector tended to operate in separate spheres.

Malnutrition is often said to be no one’s responsibility but everyone’s business. We must make it everybody’s responsibility. Leaders are needed if we want to make the legacy of the first 1,000 days last forever.

Let move in this direction all together…

* A zinc-dependent thymic hormone that regulates the differentiation of the immature thymocyte subpopulation and the function of mature T and natural killer cells and also functions as a transmitter between the neuroendocrine and immune systems

References:

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596657_eng.pdf

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00349.x/pdf

http://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/publications/Stunting1990_2011.pdf

http://www.prb.org/Publications/PolicyBriefs/HealthyMothersandHealthyNewbornsTheVitalLink.aspx?p=1

http://journals.cambridge.org/download.php?file=%2FPHN%2FPHN15_01%2FS1368980011001315a.pdf&code=9388ad17651c06a950aadfcbedad50cd

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/mar/13/undernutrition-invisible-killer-children

http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/85/2/614S.full

http://satvenandmer.hirezz.com/pdf/dha/Nutrition%20and%20Cognitive%20Development%20.pdf

http://journals.cambridge.org/download.php?file=%2FPNS%2FPNS66_03%2FS0029665107005666a.pdf&code=3d8f0f9371eabfc67ed3eff3d6c22b2f

http://advances.nutrition.org/content/2/5/377.full

http://images.abbottnutrition.com/ANHI2010/MEDIA/Cunningham_Rundles_112th%20ANRC.pdf

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(05)01274-1/fulltext

http://listas.exa.unne.edu.ar/bioquimica/inmunoclinica/documentos/protection_neonate.pdf

http://thousanddays.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Technical-Brief-4-Nutrition-and-brain-development-in-early-life-2.pdf

http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/training/2.3/2.html

http://jn.nutrition.org/content/129/2/529.full.pdf

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2011/12/08/stunted-growth-from-common-causes-threatens-childrens-later-achievement/

http://www.childinfo.org/files/low_birthweight_from_EY.pdf

http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/mdg1/atlas.html

http://www.who.int/gho/mdg/poverty_hunger/underweight_text/en/index.html